Picture yourself in the following scenarios…

How might you react if a research participant said something racist, was almost naked from the waist down on Zoom, suddenly burst into tears, or was morally offended by the choice of snacks provided by the research facility?

Or… what if one of your observers started flirting with one of your research participants, complained in front of everyone (including your boss!) that the research wasn’t uncovering anything new, or made a bigoted comment about a participant?

I recently attended a panel discussion hosted by the QRCA called “Uncomfortable Situations I Wish I Knew How to Deal With” where panelists and attendees shared frank and really uncomfortable situations they’ve encountered in the past…and then discussed different ways we might handle them.

Here are some of the strategies I learned in the webinar or have used myself…

1) Hypothesis Mapping

An executive stakeholder frustratingly exclaims “We already knew all this!”

How’s that for deflating the air from your research sessions?

Sometimes the purpose of a research study is to validate what the team already knows or believes (hey, CYA).

However, if the goal of the research study is to uncover new insights, what are some ways to help clients or observers feel like the research was a worthwhile investment of their time and resources?

My go-to method with all research planning is to find out from the project team or client what they already know, what they don’t know, and what they think they will learn to help me identify more targeted, actionable research questions.

This can be implemented formally or informally.

- Conduct stakeholder interviews

- Conduct a questionstorm

- Conduct a hypothesis mapping workshop

- Conduct an empathy mapping workshop

2) Role-Play / Rehearse

To widen your toolbox for dealing with uncomfortable situations, consider practicing how you or your team might handle different scenarios—either through role-playing exercises, rehearsing what you might say, or chatting with experienced researchers about their suggestions.

Additionally, you might decide that different situations require different approaches—depending on the research method, environment, or research topic.

If a research participant says racist or sexist comments, you might decide to just let those comments go—either because the study is being conducted one-on-one (rather than a group setting) or the participant’s beliefs are at the heart of what you want to understand about your audience.

However, in group settings, you may decide to take a different approach if uncomfortable comments are made in front of (or about) other research participants.

In my own experience, here are some approaches I’ve used:

- Know where the “hide video” and “stop screen share” buttons are when using web conference platforms.

- Unafraid to say “thank you for your time and feedback” and end the session early.

- Designate someone to run interference and support me in-session (e.g., an observer can be heard laughing in the backroom at a comment the participant just said).

- Ask the participant to clarify their statement or to expand on what they’ve just said.

- Express sympathy to the participant about their experience. When conducting CX research, I will apologize if they share a story about poor customer experience and then follow-up to ensure the participant’s issue is properly resolved after the session.

3) Session Set-Up

Sometimes your best defense is a thoughtful offense.

Before the session (or at the start of your research session), think about what you might say to ensure participants feel physically and psychologically safe—and what will be expected of them.

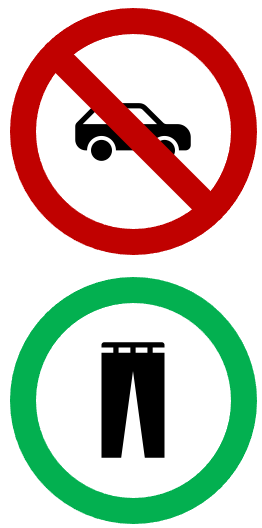

For example, I have had to explicitly tell research participants NOT to drive a car during our conversation or I will immediately terminate the session. I’ve heard other researchers explicitly require participants be fully clothed.

Consider how your facility or research study will be inclusive of different cultures and abilities. For example, if your research facility will be providing snacks to participants—ensure the options accommodate dietary restrictions and are sensitive to different cultures and religious beliefs.

4) Stakeholder Code of Conduct

A code of conduct provides guidelines and expectations to our stakeholders and research observers. That is, how do you expect everyone in the observation room to behave during and after research sessions?

In my own practice, I refer to a code of conduct as an “observer guide.”

For example, I call out in my observer guide that the backroom and one-way mirror are NOT soundproof and to keep voices low and to avoid laughing.